Craig Gauthier

“I was not always confrontational (although some people might disagree) but I was not going to let [the company] violate the union contract.”

Gauthier worked at Winchester for 23 years, from 1973 until 1996.

Early years in New Haven Born and raised in Louisiana, he first came to New Haven in 1966, just out of the military. “To me, New Haven was the most exciting place to be, politically.”

From 1966 until 1970, he worked mornings at Yale New Haven Hospital and the 3-11 shift at Pratt and Whitney in North Haven. He became interested in the Black Panther party and volunteered with their children’s breakfast program and helped to administer its clothing distribution program: “We had garages on Sylvan Avenue and Orchard Street where people could go” to pick up clothing. In 1967 and 1968, he helped organize housekeeping workers at Yale New Haven Hospital and met members of the Communist Party who worked alongside Local 1199 organizers. He “was pleased to meet progressive union people.” He joined the CP in 1970.

Back to Louisiana He went home to Louisiana in 1970 to care for his ailing mother. “In many places in Louisiana at the time, there was still ‘Jim Crow’ stuff going on.” While there, he helped start the Young Workers Liberation League, which worked with the Meat Cutters Union “trying to organize plantation workers…We took people to Washington to testify about [being] locked in to the plantation lifestyle.”

Return to New Haven He came back to the city in 1973, first getting a job as a machine operator at another company, but then went to work at Winchester in the Barrel Shop. At the same time, utilizing his Veterans’ Benefits, he attended South Central Community College: “I went to school full time and worked full time from 1973 to 1976. I loved it because it fit into my political work.”

Working with Local 609 “When the union came in, a lot of changes took place, slowly…I loved 609 because [it] had a strong presence in the Central Labor Council and in the state of Connecticut. The Machinists Union was a progressive union even though some of the leaders [were not.] 609 to me was very powerful…With 1800 workers…you bring a lot of votes [to the table and] you can move things.”

He eventually became Shop Steward for the Barrel Shop, then Assistant Chief Steward and finally Chief Steward. He became president of Local 609 in the late 1980s. “What I did to prepare for the presidency was I studied the history [of the union.] I give the initiators a lot of credit.” His greatest aspirations as president were to “be able to implement the High Performance Work Organization” [plan]“and also to get more workers actually involved in union business…We had to participate at the state level [as well], and Black members had to be involved in that.”

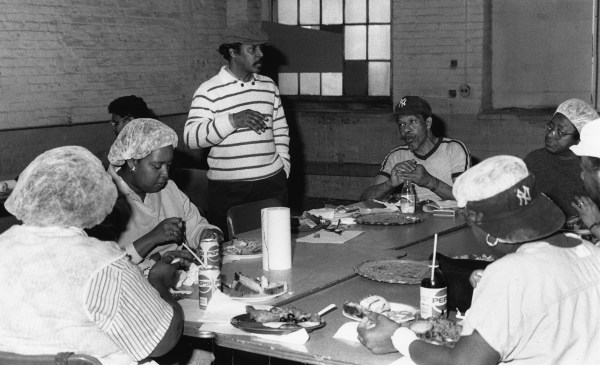

Celebrating Martin Luther King Day in the Winchester lunch room

Celebrating Martin Luther King Day in the Winchester lunch room

At Winchester, the union initiated the celebration of Martin Luther King Day every year. “The union had a certain power for the company to shut down production from 2 to 3 p.m.”

The union also started the Winchester Fund, whereby members donated money out of their paychecks to organizations such as the Dixwell Community House, the United Way and “Rev. Bonita Grubbs’ organization,” Christian Community Action. About $60,000 was donated to community groups.

Greatest challenges as Local 609 President: “I was not always confrontational (although some people might disagree) but I was not going to let [the company] violate the contract.

“The biggest problem I had [among the membership] was the trades-people because they always felt they should get all the gravy…The company would play [them] off against the machine operators…The most senior people were white men.”

“Winchester was a family. People knew each other. [It] was a place where young people could see people going to work, and leaving work talking to each other. I liked going to work. Winchester was an integral part of the community, and the people who worked there were respected: ‘Those are special workers who keep a plant running 24 hours a day, seven days a week.’”