The 1979 Strike and Craig Gauthier’s Comments

Background

The main issue in the strike was that the company wanted to eliminate the hard fought Article IV of the union contract which protected workers against daily quotas set by management. Since 1969, the company had often threatened to shut down or move out of New Haven to back up its demand for increased production with no increase in pay.

The company spared no expense to break the 1979 strike and Local 609: it obtained an injunction that mandated no more than 20 picketers at one time and required them to register with police; it took out full pages in the local papers; it engaged the local police force in escorting strike-breakers across the picket lines. Arrests were made in August of 7 picketers. Thousands of workers from throughout New England came to New Haven to march and support the strikers at the end of the month. New Haven’s Mayor, Frank Logue, ordered all access to the plant closed in order to end the confrontations between police and strikers.

On January 20, 1980, after six months on strike, Winchester workers voted to accept a compromise contract, which provided some protections for elderly or disabled workers if they couldn’t meet speed-up requirements, as well as higher pay and improved pension and medical benefits for all. But the company won the right to set production standards, and to fire workers that it alleged were unproductive if an arbitrators’ decision was not reached within 45 days.

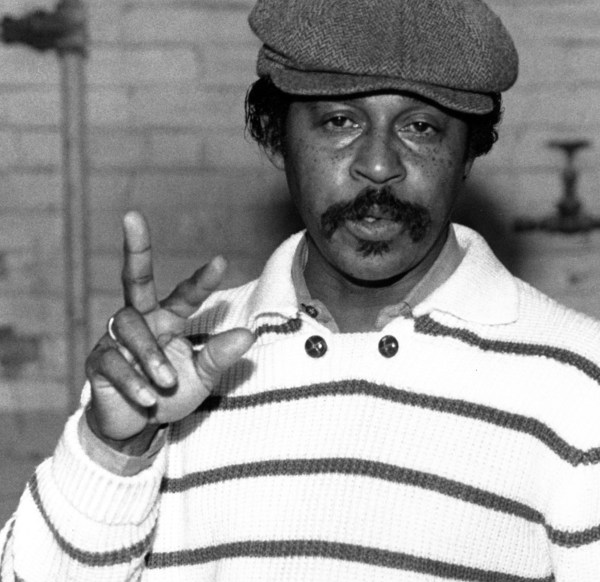

Craig Gauthier on the 1979 Strike

“It was a hard strike because the company had the media and the city on their side…The company felt that the union had become too powerful because of its strength within the Central Labor Council and the state. It wanted to break the union’s strength.

When the union learned that the company was bringing in workers by bus to cross the picket line, “we decided that we weren’t letting the scabs in.” Some of the strikers started rocking the bus. Leonard Gallo, then a New Haven police officer who later became the Police Chief in East Haven, led a “team” who “attacked us; they cornered us between two cars and beat us up. I ended up in the hospital.”

Still, he felt that the strike “not only brought the union together stronger, it brought the community together stronger.” The community mobilized to support the strikers. “We couldn’t have survived if we didn’t have the Central Labor Council and the community behind us.”