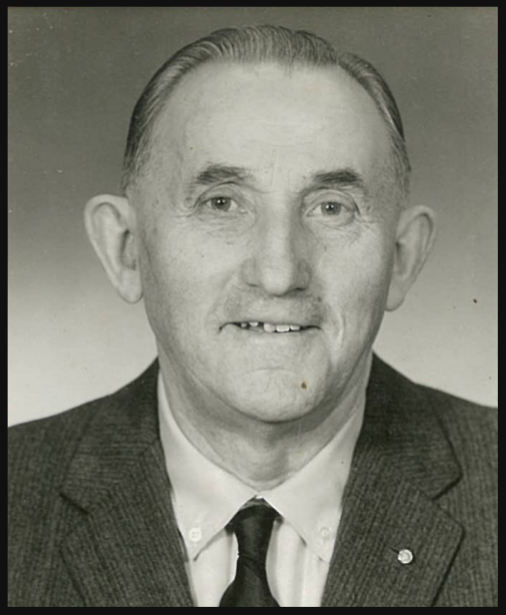

Martin Francis Looney

“[My father] would have said that the last nine years” (after the union came in) “were so much better than the first 16.”

—Connecticut State Senator Martin M. Looney

This photo of my father, Martin Francis Looney, was taken

at the time of his retirement from Olin-Winchester in 1965.

He operated a forklift there for 25 years, 1940-1965,

interrupted by U.S. army service for six months, September

1942-March 1943.

He was born March 9, 1900 in Miltown, Maltbay, County

Clare, Ireland, emigrated to the U.S. in 1927, and died in

New Haven on April 29, 1972 at age 72. He lived in New

Haven from the time of his arrival in the U.S. until his death.

My mother, Mary Mescall Looney, was born April 22, 1910

in Cooraclare, County Clare, Ireland, emigrated to the U.S. in

1929, and died in New Haven on May 28, 1991 at age 81.

They were married on June 20, 1942 in Brooklyn, NY, where

my mother lived from the time of her arrival in America until

her marriage. They settled in New Haven where I, their only

child, was born in 1948.

—Connecticut State Senator Martin M. Looney

AUGUST 16, 2017

The union was important for the Dignity of the Workers:

Martin Francis Looney, Union Organizer

When the International Association of Machinists began its drive at the Winchester plant in the early 1950s, Martin F. Looney became an active union supporter and organizer. His son, Connecticut State Senator Martin Michael Looney, remembers:Led early on by William S. Boak, “the personification of management anti-union efforts” and his sucessors, the company showed “clear favoritism toward those they saw as reliable anti-union votes.” Looney had been counseled by friends and family who correctly feared company retribution “not to be so active” at his age, but, “he believed strongly that the union was important for the dignity of workers,” and that “for industrial workers, there really was no way to avoid discrimination and abuses without it.”

As his friends and family feared, after the first International of Machinists union vote failed in the early 1950s, in punishment for his activism, the company transferred Looney to a different job, moving freight. In his early 50s at the time, he was now “working with men twice his size and half his age.” Recognizing the reason for his transfer, and the fact that “helping him was helping the union,” the younger men, mostly African Americans, did what they could to ease the burden of the most strenuous tasks, “without drawing the ire of management."

Mrs. Looney worried about her husband during this time “because she saw the physical and emotional toll” the work itself and the struggle for the union were taking on him. Looney had high blood pressure and “it was a difficult couple of years.”

In addition to wages, workers were concerned about safety issues and about discrimination against older workers. As they became increasingly aware of the “company strategy of divide and conquer” (pitting different classes, ages and ethnicities of workers against one another), “they didn’t want to be complicit in what it was trying to do and were finally willing to take their long-term interests into account, rather than the short-term.”

After the union was finally victorious in 1956, Mr. Looney got his old job back within a couple of months. Sen. Looney recalls the “great celebration and joy” his father experienced because of the victory, and notes that “our family’s standard of living definitely improved.”

Martin Francis Looney, Union Steward

For nine years after the union victory, until his retirement in 1965, Looney was a Local 609 steward. As an advocate for workers, he considered that the “highlight” of his tenure in this position was his handling of a complaint by an African American worker who had been “racially slurred” by a high-level manager. Looney documented the complaint and saw it all the way through the grievance process. The manager had to submit a written apology which was posted in the work-place.Mr. Looney worked at the plant during only one of the big strikes after the union victory. In 1962, the issues were, according to his son, “wages, the level of increase being offered, benefits in terms of the health plan, work rules and protections of people in certain job categories.”